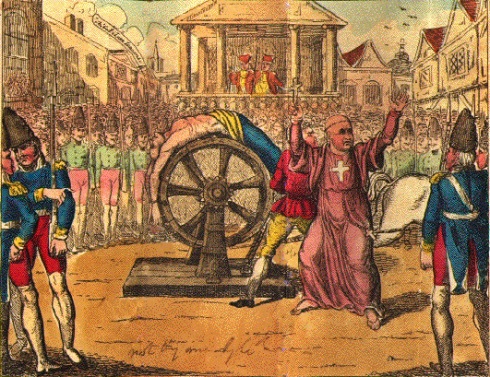

After 1764, the Huguenots were increasingly accepted into French society, although without any legal edict decreeing this acceptance. However, persecution was fresh in popular memory. The illustration shows a Protestant being broken on a wheel in Toulouse in 1762.

Edict of Versailles, 1787

In 1787, Louis XVI signed the Edict of Tolerance, also known as the Edict of Versailles. This edict overturned the 102-year old Revocation of the Edict of Nantes (the Edict of Fontainebleau).

This came about after French statesmen and philsophers — as well as American visitors to the French court, such as Benjamin Franklin — pressed for legal rights and religious liberties for Huguenots.

Although Catholicism was still the state religion, the Edict of Versailles enabled non-Catholic worshippers to practice their faith, whether they were Huguenots, Lutherans (in the northeast) or Jews.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, 1789

The French Revolution began in 1789 and lasted ten years.

In 1789, the National Constituent Assembly wasted no time in drawing up the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. This declared all French citizens ‘equal in the eyes of the law’.

Some American Protestants object to the Enlightenment — wrongly, in my opinion. This declaration, as is true of the Bill of Rights and Constitution of the United States, was essential for citizens’ legal rights and religious practice. It is staggering to think that an American literalist living in the suburbs could find this objectionable because such documents are secular or were drawn up by people who didn’t share their beliefs. That is a curious attitude to have, especially as those men enabled them to live in the freest country in the world (until 2001, at any rate). Such documents have to be secular, otherwise, we run the risk of compromising liberty, which inevitably results in persecuting others, as history (including this series on Huguenots) has shown.

The Right of Return, 1790

One year after the 1789 Declaration, the French government invited descendants of Huguenots to return to France with the promise of full citizenship:

All persons born in a foreign country and descending in any degree of a French man or woman expatriated for religious reason are declared French nationals (naturels français) and will benefit from rights attached to that quality if they come back to France, establish their domicile there and take the civic oath.

However, it is thought that not many Huguenots returned. Nonetheless, this was an important concession on behalf of the government.

The Musée Protestant (Protestant Museum) states that by 1791 Protestants in France were satisfied with their rights (emphases in the original):

They were given civil equality, freedom of conscience and freedom of worship.

The Declaration of Human and Civil rights on 26th August 1789, granted them freedom of conscience and the Constitution in 1791, freedom of worship.During the Revolution years, the behaviour of the Protestants was not consistent. Individuals responded differently to the Revolution. Many Protestants took part in Revolution Meetings, but there was no “Protestant group”.

During the Reign of Terror, the Dechristianisation phenomenon – September 1793 to July 1794 – did not have a great effect on the Protestant community, even though worship was suspended almost everywhere. But it did mean most pastors temporarily stopped their activity. After Robespierre’s death, on 9 Thermidor year II (27th July 1794), churches were re-opened and freedom of worship proclaimed.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, 1793

This Declaration put more of an emphasis on equality of all citizens, in an attempt to address social inequality:

Article 21 states that every citizen has a right to … work and society has a duty to provide relief to those who cannot work. Article 22 declares a right to education.

The 1793 Declaration made the language of the 1789 Declaration more specific:

The declaration explicitly states the freedom of religion, of assembly, and of the press (article 7), of commerce (article 17), of petition (article 32). Slavery is prohibited by article 10 which states “Every man can contract his services and his time, but he cannot sell himself nor be sold: his person is not an alienable property.”

Organic Articles, 1802

When Napoleon Bonaparte came to power, he was intent on eliminating any loopholes in the law with regard to religious practice.

His Organic Articles of April 1802 had 121 articles concerning worship. Seventy-seven related to the Catholic Church and 44 to the Protestants.

received the freedom to worship, but they were to have no national synod, which may have created a state within the state. Rather, the law established regional church organisations known as consistoires.

Consistories are normal, worldwide practice for Reformed (Calvinist) denominations as synods are for Lutherans. These were devised by church leaders centuries ago. It’s important to know that Napoleon did not devise this polity; it already existed. It seems that he did not want the Protestant churches to stray from this system of governance.

In any event, it took from 1559 to 1802 to fully guarantee Huguenots the right of worship in their own country.

Later developments

In 1889, the French slightly modified their citizenship law with regard to descendants of Huguenots who wished to move to France and become citizens of that nation. The 1790 Right to Return still applied, but became more formalised, involving a decree for each person as well as an oath.

In 1945 France revoked the automatic right of Huguenot descendants to French citizenship.

In 1985 — the 300th anniversary of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes — the then-president François Mitterand formally apologised for the persecution of the Huguenots. La Poste issued a commemorative postage stamp in their memory.

Tomorrow: The Huguenot colony in Brazil

2 comments

August 23, 2013 at 12:38 am

KDP

Check out this website to be inspired by a Huguenot family:

http://www.archive.org/stream/memoirsofhugueno00byufont#page/n7/mode/2up

LikeLike

August 23, 2013 at 6:29 am

churchmouse

Thank you very much, KDP — greatly appreciated!

I shall look forward to reading this volume and blogging on it in future.

LikeLike